Last Updated on May 13, 2021 – 7:49 PM CDT

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune: Read More

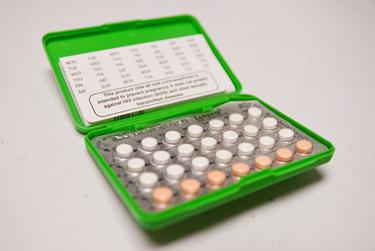

Birth control pills available at a Planned Parenthood in Austin.

Credit: Todd Wiseman for The Texas Tribune

Sign up for The Brief, our daily newsletter that keeps readers up to speed on the most essential Texas news.

When Jazmine Johnson was in high school, she suffered from heavy periods that were so debilitatingly painful, it affected her school performance.

Her medical insurance at the time was provided by the Texas Children’s Health Insurance Program, known as CHIP, which provides health care to adolescents whose families are low-income but make too much to qualify for Medicaid. CHIP provided coverage for her medicine, doctors appointments and other medical needs but unlike Medicaid, it typically does not cover the cost of birth control — something that Johnson needed to regulate her menstrual cycle.

“I started having to miss school,” said Johnson, now 19 and a junior at the University of Texas at San Antonio. “I was trying to focus really hard on getting scholarships and making sure my grades were OK. But it’s hard to focus on the things you should like in high school when you can’t even get out of bed for a week out of the month.”

Texas, a state with the nation’s ninth highest rate of teen pregnancy, is one of only two states where the state children’s insurance program does not cover contraceptives to prevent pregnancy for low-income teenagers. The program does make exceptions for teens seeking birth control for medical issues like anemia, endometriosis, and heavy periods, but it requires multiple levels of authorization from insurance to verify it isn’t being used to prevent pregnancy.

“What we hear over and over again from both providers and from CHIP clients is that even when they do have a documented medical need, (CHIP) creates so much red tape and documenting and proving that medical need,” said Jen Biundo, the director of policy and data for the Texas Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy.

Johnson, who grew up in Jefferson, said while her medical condition made her eligible to get coverage under CHIP, she struggled to get her birth control refilled consistently because of all of the red tape. Eventually, she sought out a family planning clinic to get a more permanent solution.

To access birth control, low-income teens have to turn to more limited state programs. The Healthy Texas Women’s program, which provides free coverage for health care around pregnancy, can offer birth control for teens on CHIP, but they would have to forego all other types of health coverage. They also could use the Texas family planning program, which provides low-cost reproductive and planning health care, but would have to be able to travel to one of the roughly 200 clinics across the state.

Critics of the restrictions say this costs Texas taxpayers far more money, as the state pays for the Healthy Texas Women’s program in full. In comparison, the federal government matches more than 75% of all services covered in the children’s health care plan.

Last session, a bill to expand CHIP to cover contraceptives passed the Texas House with bipartisan support, but died after the Senate did not take it up. This session, House Bill 835, a similar bill authored by Rep. Donna Howard, D-Austin, has not even received a committee hearing in the House — and it may be too late. By midnight Friday, House members have to grant preliminary approval to bills written by its members, with the exception of bills on the local and consent calendar.

“We’re one of only two states that doesn’t do this,” Howard said. “There’s just no logical reason for it and no rational reason for it. Certainly, it does not make fiscal sense to not include this.”

Howard said there hasn’t been an articulated reason for the bill’s lack of movement, but she has seen pushback against bills that give minors too much power without including parental consent. But Howard’s bill would require parental consent for their kids to access contraception.

“There is just a sense that anytime you’re talking about minors, if you’re not having the minors’ parents consent to it, then you’re overreaching,” Howard said.

The bill’s advocates also point to the effectiveness of birth control in preventing teen pregnancy.

In 2018, almost 1,600 Texas teens enrolled in CHIP experienced pregnancy, according to a report from the Texas Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. Teen pregnancy has consistently decreased over the past 30 years nationwide, partially due to higher rates of birth control use.

Biundo said because minors near family planning clinics can still access birth control, the problem with CHIP isn’t a question of whether contraceptives should be restricted from teens. It’s a question of how much the state wants to pay.

“We’re basically just leaving a huge amount of federal money on the table,” Biundo said of the money the federal government would match for birth control under CHIP rather than state programs.

Biundo said Texas family planning clinics are also centered in population hubs, and 74% of Texas counties don’t have one of these clinics.

Texas pediatrician Maria Monge said the lack of easy coverage from CHIP has directly impacted her patients. One of Monge’s 12-year-old patients was rushed to the emergency room for heavy menstrual bleeding, and hospital doctors prescribed her birth control. But as CHIP took too long to provide coverage, the patient’s bleeding worsened, and she had to receive a blood transfusion two weeks later.

“This is a health equity issue more than anything else,” Texas pediatrician Monge said. “We have patients who, because of the way that hormones aren’t covered but require authorization, need blood transfusions. Whereas private insurances, for these same medications, almost never require that same level of scrutiny.”

Because of the patchwork of programs providing birth control and the delay insurance authorization can cause, Erika Ramirez, the director for policy and advocacy for the Texas Women’s Healthcare Coalition, said the bill is important for women’s healthcare when she testified in favor of CHIP’s expansion in 2019.

“Navigating multiple programs is a barrier to access, and puts the burden on the young woman and her family,” Ramirez said.

Shannon Najmabadi contributed to this report.