Last Updated on May 2, 2016 – 4:12 PM CDT

For the last few months I’ve been thinking about how to start this column, but looking for a beginning has been like trying to find that one string in a knotted ball that is the key to making it release its tangles. Pull the wrong one, and the strings tighten into a worse mess. I’ve been tugging on those wrong strings, grappling with beginnings that made my thoughts snarl around each other in a tighter ball of confusion.

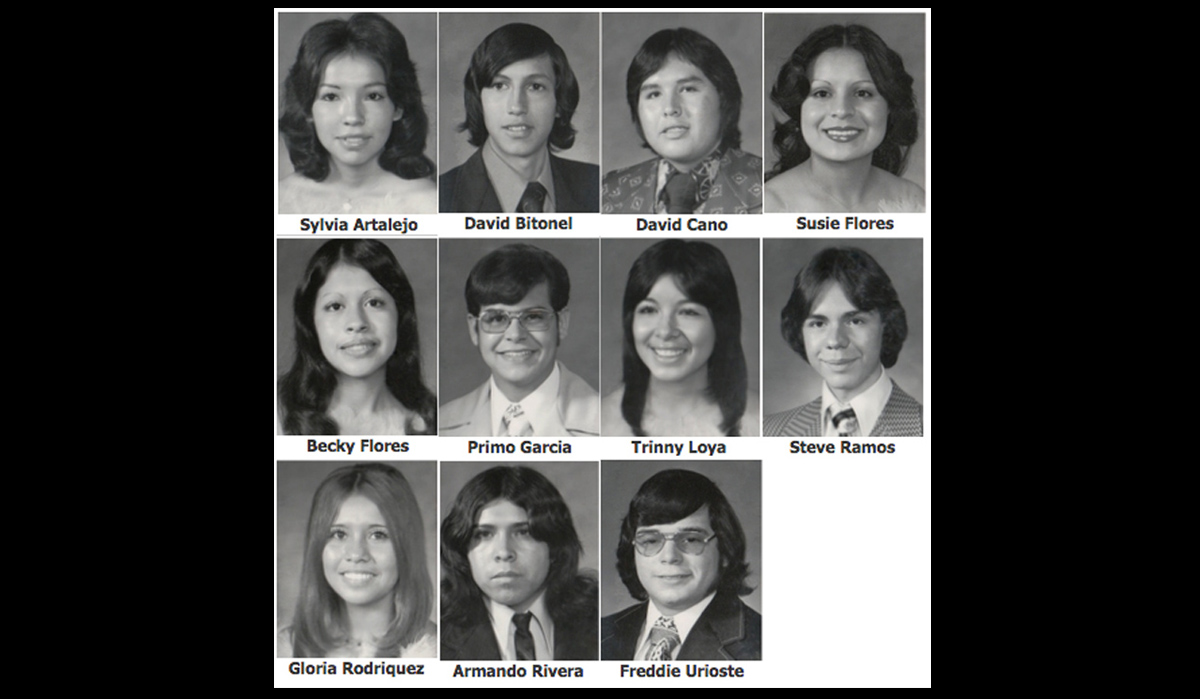

So what the heck. I’ll just plunge in. A few months ago, I was at a soccer game, and I heard the boys on the bench speaking Spanish to each other. Nothing wrong with that. I speak Spanish, too, but it made me think of how much the school’s demographics have changed since I was there in the 1970s. There were 11 Hispanics in the class of ’76, and I was very aware of it.

Before anyone thinks this column is about the white students treating us badly, just back up. It has nothing to do with that. It’s about how it felt to be Hispanic in a white world. At least to me. Granted, I’ve always been an over thinker. Some people go through their days never wondering about anything or questioning anything, but I’m a nosey guy. I had to learn how to meditate to stop my brain for a few consecutive minutes so I would have a chance to fall asleep. The squirrel cage never stopped turning, and there has always been a lot of loud rattling up there.

So try to understand why my ears perked up when I heard those boys speaking Spanish. It’s because when I was in high school, we didn’t do it. Us Mexicans were sprinkled throughout the classrooms, so it was unlikely there was another Mexican sitting beside you learning how to diagram a sentence or how to factor in Coach Ward’s algebra class. Who were we going to speak Spanish to?

Like most of us Mexicans attending Dumas High School back in those days, we were raised in traditional Spanish-speaking homes. Once you entered my front door, you were in Mexico. I had never seen meatloaf or chocolate pudding until I started school, and I stared at them on my partitioned lunch tray like they were something exotic — and to me they were. In my house, we had carne guisada, sopas, pollo con mole and, of course, beans and rice. The kitchen was permanently scented with flour tortillas cooking on the comal, and those tortillas were our utensils. Forget spoons. By the time a Mexican child is two years old, he can roll up a piece of tortilla and use it to chase food around his plate, not leaving one grain of Spanish rice.

My grandmother cooked in clay pots, those cazuelas de barro she would stock up on during our yearly trips to Laredo and Mexico to visit family. When I’d go to a white friend’s house, it was like entering another country. I know, I know. Most kids probably didn’t give it a second thought, but this searching mind did, and I know some of my Mexican friends did, too. It kindled questions. Questions like which world do we belong to? We lived in Mexican homes, but when we walked out of them, we were in a white world. None of my white friends ever treated me any differently than they treated others. I don’t think they gave us being Mexican one thought, but my mind was always spinning like those bingo machines with all the tiles banging around inside of them. I wondered about everything, and I wondered where did I belong.

It was so different back then. The Mexican population in Dumas was small, and we all knew each other. Going to the Mexican dances was a family event, and Mexican traditions were observed. You want to dance with a girl? You ask her parents first. You want to go out with a Mexican girl? You’d better have enough money to pay for her little brother’s movie ticket because he’s going with you, too. The question thrown around all the Mexican homes was, “Qué dira la gente?” Translated, “What would people say?”

As high school graduation approached, few of us Mexicans were prepared. We maneuvered through the applications as best we could because our parents and grandparents didn’t have a clue what to do. If you were a Mexican girl, it was likely that your traditional Mexican father would say, “Why do you want to go to college? You should get married.” We fumbled through the process, mostly clueless of how to get scholarships or financial aid.

I know this has been a rambling column, but I have yet to figure out how to explain what it was like to grow up Mexican when Dumas was white. Many of us, if you count about 35 Mexican kids in high school as many, played sports, were in band and choir and took part in other activities. Angie Bitonel was a cheerleader, homecoming queen and Most Beautiful. Betty Puelma was Dani Demon. Connie Ruiz was a twirler in band. Their popularity shows there was no prejudice that I know of toward us. The confusion was all mine. I left my Spanish-speaking home in the morning after eating a breakfast of chorizo and went to school with friends who had just polished off bacon and eggs. And I wanted to be like them. I wanted to eat meatloaf and spaghetti. I would plead with my grandmother to just open a can of SpaghettiOs for once, but she’d huff and push a plate of calabazas in front of me and slap a couple of tortillas down beside it.

So when I heard those boys speaking Spanish, it made me smile, and it made me happy for them. They won’t know what it’s like to live in a home so different than the world outside of it. They won’t know what it’s like to leave Spanish at home and not speak it until you return. They won’t know what it’s like to explain to your white friends you can’t go out because your family is in mourning over the death of a family member. Go out? “Nombre, qué dira la gente?” During the periods of mourning in those traditional Mexican homes, there was no TV, no going to the movies, nada. You’re in mourning. You’re supposed to be sad. Well heck yeah I was sad. I couldn’t go anywhere, and I didn’t even like my great aunt who died. And I won’t even get started about the holy water fonts in the bedrooms and an altar with a burning candle on top of every dresser. It’s a wonder all the Catholic Mexican homes didn’t burn down, but how could they? We were all stuck at home in mourning over some tía or tío back in Mexico who kicked the bucket.

Dumas has changed. El Vaquero occupies the old Anthony’s, a department store long gone. Up and down Dumas’ streets, Mexican-owned businesses thrive. I hear Spanish spoken almost everywhere in a town where it was once spoken only in a few homes. I’m glad the Mexican kids have others they can speak Spanish to. I even hear the white boys in the baseball dugouts joking around in Spanish. It’s awesome they will grow up exposed to a culture that isn’t their own. Just as I and the other Mexicans who grew up in Dumas 40-plus years ago were exposed to a culture that wasn’t ours.

Today, I still speak Spanish. I think in Spanish most of the time, and, frankly, I prefer to cuss in Spanish. Oh, and let me tell you that the Spanish terms of endearment have no equal. Mi cielo, corazon and amor convey much, much more than honey or sweetheart. Cielo means sky, so when you call someone you love “mi cielo”, you’re telling them they are an endless expanse of peaceful blue. It makes you want to speak Spanish, doesn’t it?!

I think many American-born-and-raised Mexicans wonder where they belong. In Mexico we’re told we’re too American. In the U.S., we’re often told we’re too Mexican. Con razon we’re so confused. And, yes, we mix the languages to the annoyance of the snobs who think it’s low class. How many times when we were kids did a parent ask, “You want the chancla?” Trust me, you don’t want the chancla.

So 1,500 words later, I’m still confused. I’m writing in English, but I’m thinking about the sopa de fideo waiting on the stove at home. You’re welcome to join me. Bring the meatloaf.

As a child I would often flip through the pages of this yearbook (1976). I would try to imagine the high school experience that my father had based on the stories that he would tell us (I have 1 brother and 1 sister). Then I would examine the faces of each of his classmates and wonder what kind of person they were. Were they nice? Were they mean? Good, bad, or indifferent these experiences helped mold my father into the man that he is today. Now as a father myself, I feel a sense of pride in the accomplishments of both of my parents (class of 1976 and class of 1979) and I believe that these experiences have had a lasting effect on my life.

Michael Cano

What an article…..I’m from a small town, Petersburg, Texas population back then (60’s-70’s) around 1,500 and now I’ve resided in Lubbock Texas since 1980 and I love reading articles such as this one. I posted it on my facebook for others to read. It’s really weird, with Trump running for President and some of my childhood friends are voting for him and I on the other hand, thinking, WTH happen to the person\people I knew back in the day. One of my classmates asked me last week after speaking to her regarding the health of her mother, she asked, “J.R. were people prejudice back then when we were going to school, because I didn’t see it? (she is white)” This question came up because of the hoopla of Trump and how people have different opinions about him. It goes back to your story, we were all different, but were the same to a certain extent. My answer to her was pretty simple, I told her remember the scene in La Bamba where Richie goes to pick up his girl friend at her house and the father will not let Richie inside or let him see his daughter…..Well that happen to me, but Richie’s response was made for TV, my response from the father of my friend was way over the top, something that started like….”Do you think I’m going to let my girl go with some wetback Mexican to the prom, over my damn dead body….” That was just the start and I was only a freshman, and then going to the prom without a date, everyone knew I was taking her, and I showed up without a date, and then to be spoken to like that…. I was a kid. I never told anyone, except a couple of friends. But yes, we had those who looked down on us, and they still do, the difference is, now we respond back. But getting back to your article, I tell my children and even my wife of the past, and they just couldn’t comprehend until I read them this article. I’m proud of my little town, last year was the first time they voted a Hispanic on the City Council. And this next month they may end up having a Hispanic Mayor also. Yes things have changed. It’s also my understanding, certain folks who reside in my small town didn’t feel their child should go to the local school, so they moved them to the next city over. Was it the academics they offered at each school or because the population of the school changed so much? I’ll just leave it at that. Nothing will change until we all register to vote and actually go out and vote to make that difference. Again, thanks for writing the article, it brought back some good memories, it woke me up, and it was a nice read. PS I know David Bitonel & Anjie

Comments are closed.